Posts

LA Social Science 2021 Summer Course Previews: Web Development and GIS for Social Change in Asian American Studies

As summer 2021 approaches, LA Social Science will be highlighting…

LA Social Science “Summer Take-Over” with Drs. Haley and Hong Discussing Abolition and Feminism

LA Social Science presents its first "Summer Take-Over" featuring…

LA Social Science Summer Course Previews: Asian American Studies Department Courses in 2020

As summer 2020 approaches, LA Social Science will be highlighting…

Any Plans for the Summer? Enroll TODAY in an Online UCLA Summer Course

Have you always wanted to take a course in the social sciences?

Did…

The Coronavirus and the Humbling of America

Professor Vinay Lal, UCLA Professor of History and Asian…

The Singular and Sinister Exceptionality of the Coronavirus (COVID-19)

Professor Vinay Lal, UCLA Professor of History and Asian American…

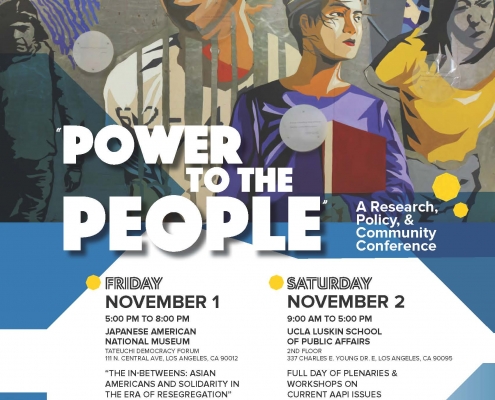

Asian American Studies Conference Commemorates 50th Anniversary at UCLA This Weekend

The UCLA Asian American Studies Department, the UCLA Asian American…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Dr. Karen Umemoto

Dr. Karen Umemoto is a professor in the Department of Asian…