By Lara Drasin

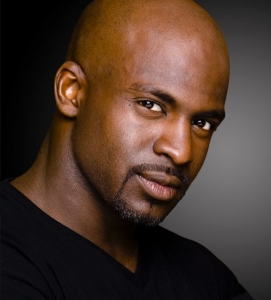

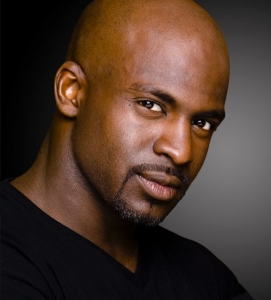

Bryonn Bain is a UCLA professor jointly appointed in the African American Studies and World Arts and Cultures/Dance departments, as well as a prison activist, spoken word poet, hip-hop artist, actor and author. He is the founder and director of UCLA’s Prison Education Program, which was launched in 2016 to create innovative courses that enable UCLA faculty and students to learn from, and alongside, participants incarcerated at the California Institute for Women (CIW) and Barry J. Nidorf Juvenile Hall (BJN).

Rosie Rios is the administrative director of UCLA’s Prison Education Program.

Part 1 of the series will first focus on the interview with Professor Bain

LD: What do you [Professor Bain] tell people you do when you first meet them?

LD: What do you [Professor Bain] tell people you do when you first meet them?

BB: It depends on the context. On this campus, I think students identify me first and foremost as a professor, and as the director of the Prison Education Program. But before I was any of those things, I was an artist; I was an activist; I was an educator. I really am excited about the intersection of those identities, where they come together and create sparks and possibilities for transformation.

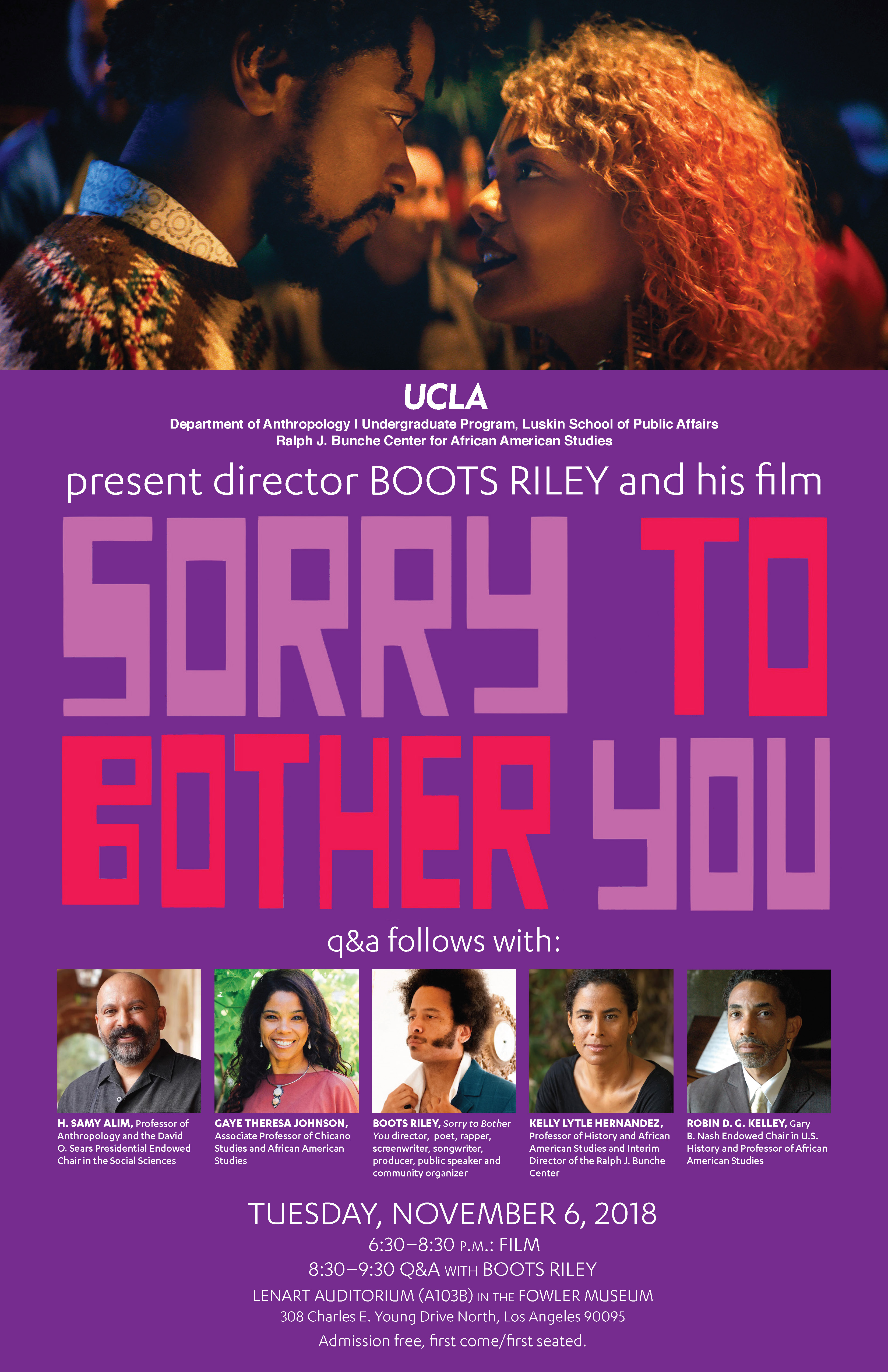

I’m inspired by people who consider themselves to be change makers. I’m inspired by people like Robin Kelley, who recruited me to come [to UCLA]. Cheryl Harris. I’m inspired by folks who see that when you bring together ways of understanding the world that aren’t often put together, all these amazing possibilities exist.

I’m also the son of immigrants, from a little island in the Caribbean called Trinidad and Tobago. My father was a storyteller — he was a calypsonian — and so I have some of that in me. I’m a storyteller. It’s part of my artistry as a poet; as an actor; as a theater maker. That’s part of my identity.

My mother is a healer. She’s been a nurse for 40 years. I think from her as a healer, and having all these aunts who are healers, I was definitely inspired to be an activist and to use whatever skills and talents and time I have on this planet — between womb and tomb — to try to impact the lives of those around me. So I think that’s where my desire to try to make change happen through activism comes from. I think there’s an intersection between arts activism and education that is at the heart of who I am.

LD: Tell me about your work within the different contexts, [Professor Bain].

BB: We do a lot of work in correctional facilities. We have offered courses at two correctional facilities in California, and we’ve taught five courses between the women’s prison and the juvenile hall. At the end of this year, we will have taught seven more. In those spaces, we’re here to represent students and faculty, to create opportunities for incarcerated students and students at the university to engage in higher learning and education together. So, they see me as a professor.

When I’m in a performance space I’m an actor, I’m looking at scripts, and I’m just one of the folks in the room who’s trying to tell the story together. We’re storytellers.

We all have these different layers, right? It’s not just me, or just [Rosie Rios, Administrative Director of the Prison Education Program], or just you.

Kimberlé Crenshaw and W.E.B. Du Bois before her were onto something when they talked about a double or triple or multiple consciousnesses. It’s dealing with, for example, the NYPD who didn’t believe me when I told [the officer] that I was a law student; didn’t believe me when I told them that the Sony VAIO laptop I had in my bag was mine — not that I stole it — or the public defender who told me that rather than believing my resume, she was more inclined to believe that I had a lengthy rap sheet. I think if we look at each other as full human beings, we’re multidimensional. People are not like those old school TV sets, where you could change from one channel to the next. Our identities all flow into each other, right? And so we have to get comfortable understanding that people have these multiple parts to themselves.

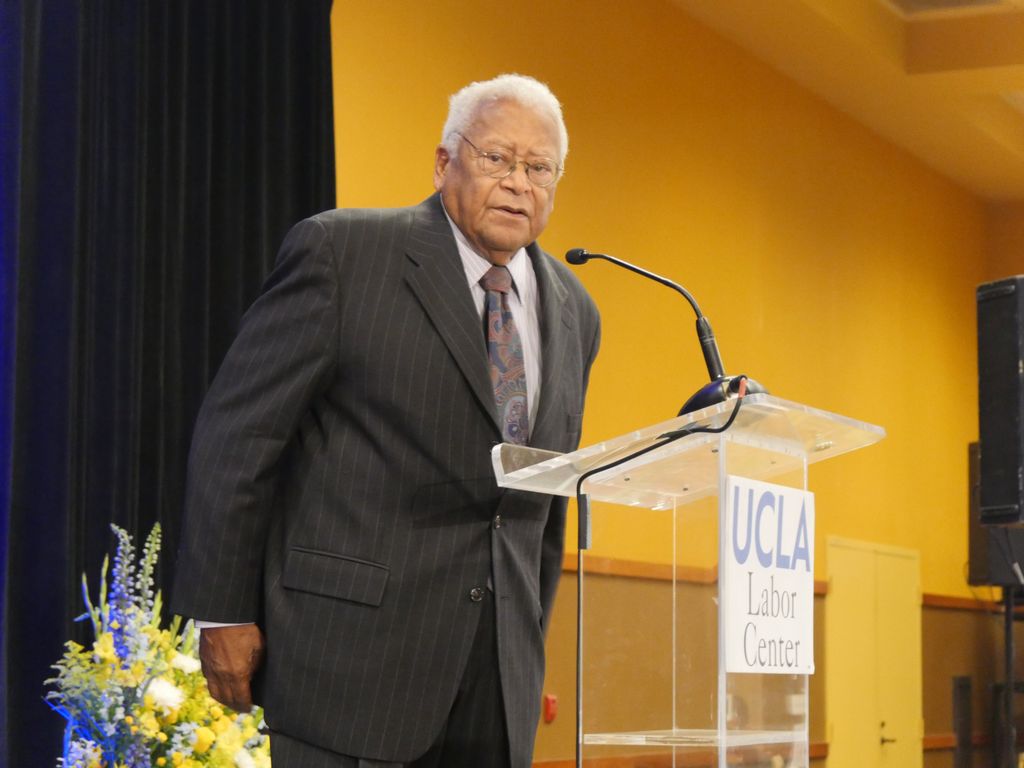

Members of the UCLA Prison Education Program team. Front row: Dianna Williams, Daniel Ocampo, Lyric “Day-Day” Green-Brown, Rosie Rios, Joanna Navarro. Back row: Gabrielle Sheerer, Dominique Rocker, Bryonn Bain, Derrick Kemp.

“…I think we’ve become numb and desensitized to a lot of the suffering that’s around us, and I think art is one way to say ‘No, wake up.'”

— Professor Bain

LD: How are the arts initiatives you bring to prisons received — not only by the students — but by everyone that you’ve had to go through in order to make this happen? Do you present it as a healing modality? How do you justify it to them when so many institutions still don’t take the arts seriously?

BB: This is one of the few countries where the arts are not taken as seriously as the rest of the world takes it. And at the same time, we wouldn’t think about Los Angeles or California as being the same without Hollywood, right? So there is a certain amount of respect for the power of storytelling at some level. I think it’s also important for us to understand that there are other ways for the arts to live and to feed us. Prisons are a public health crisis for many reasons, one of them being that we have more people in prisons with mental health issues than we have in mental health institutions. So prisons are being used as a way to deal with mental health and public health issues that they are not effective at dealing with. Drug addiction is a disease — it’s a public health issue according to the Center for Disease Control — and we’re treating it like it’s a criminal justice issue by locking people up and denying access to what they need. And a lot of people still have access to many banned substances that are available in prisons. So I think we have to really expand our thinking about that. But I think the arts are a way to open people up to see things in different ways. There are many metaphors for art: art as medicine, art as healing, art as a weapon, a tool for resistance to fight oppression. There is no movement for justice that did not have the arts as a part of it.

Anne Bogart talked about art as dealing with the world of aesthetics. And so when you think about what it means to be aesthetic, you think about what “anesthetic” or “anesthesia” is, right? Malcolm X talked about how when you go to the doctor what they do is put Novocaine in your mouth right so you could suffer peacefully, that you can actually bleed all over your mouth and they’ll tell you you’re just fine. So an anesthetic, or “anesthesia,” is actually about numbing your senses: making it so that you don’t see smell, taste, or touch with the same level of intensity. It puts your senses to sleep. So aesthetics should be the opposite of that. An aesthetic should wake up the senses. I think about art as being an alarm clock, waking up the senses to things that we may have become numb to. I’m from a city where 20 million people can walk down the street — and there’s lots of love in the boroughs — but there are certain parts of Manhattan that are not like the block I’m from in Brooklyn. Somebody can be dead on the street and 50 people could walk over the body before anybody even asks if you’re okay. So I think we’ve become numb and desensitized to a lot of the suffering that’s around us, and I think art is one way to say “No, wake up. Human beings who share your experiences, and your oxygen, and your water supply, and in many ways are part of the same organism, are going through and experiencing things that we need to be awakened to.” I think art has the power to do that, to wake us up to realize that we actually have work to do. The social sciences are a direct connection to the arts, because it’s one place you can go to actually dig into the reality of the world: to actually figure out what change has to happen based on the research that many of my colleagues here are doing.

LD: That’s a good segue into my question about the arts and science. They’ve been separated for so long, even though we know that they’re not actually separate. I know that recently you received a joint appointment to the World Arts and Cultures/Dance department. Do you know if there are a lot of professors on campus that have appointments in both a social or life science department and an arts department?

BB: I heard of one other before me who was in Chicana/o Studies and also in World Arts and Cultures/Dance. But beyond that, I don’t know of any others. I know that Robin Kelley and Scot Brown are both African American Studies and History, and they also have an affiliation with the Global Jazz Studies program. Robin Kelley wrote the brilliant biography of jazz musician and legend Thelonius Monk, and Scot Brown does a lot of work around funk. So they have this connection between history, the arts and music that I think is really powerful.

Tricia Rose wrote one of the first scholarly books around hip-hop in 1994, Black Noise, and I had a chance to study with her at NYU as a grad student. I think my own experience was a little different because I identified as an artist. So while I wanted to study art to understand it, I also am a practitioner — I am a culture maker, a culture worker. It’s equally important to me to study the history, the culture, and the politics of the artistic media that I engage, and to develop my own craft.

I think there’s room for all kinds of art at all levels. But if we only have art that is about justice that is of a very low quality, we’re not helping the movement — we’re actually hurting the movement. So I try to challenge my students to explore terrain that they may have not experienced before, to think critically about the artistic practice and to think about the relationship between their art, the work they’re making and the world they want to build. I do that because I had amazing teachers and mentors who did the same thing with me. If you had to pay royalty checks for everything you take from your professor’s syllabus I would owe Lani Guinier a check every week. She is a brilliant, brilliant teacher who encouraged me to use collaboration in classrooms, to use creativity in the classroom, and to think critically in the classroom. So, those are things that are at the heart of how I connect to the arts and the social sciences.

“It’s a different time now and there is a whole lot that has not changed and needs to change. But I think our consciousness is expanding. I think the voices of people who were formerly incarcerated and are currently incarcerated are moving toward the center of the movement where they should be.” — Professor Bain

LD: It seems like more people are accepting the fact that the stories we tell, including the media and entertainment we consume and create, are impactful in how they represent our lives and shaping who we are. Obviously, whenever there are these big shifts, we see it at different levels, and we sometimes see it commoditized or hijacked. What’s been your experience in observing this shift?

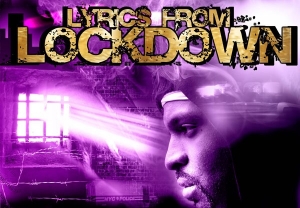

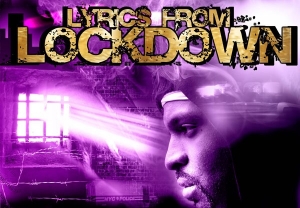

BB: We’re in a time where there’s more of a movement to do many of the things that some folks realized need[ed] to happen 20 years ago, but there was no movement in place. Without a mass social movement, it’s very difficult to make change that is lasting, systemic and happens at an institutional level. So that is the biggest difference. I finished law school and I had a really unbelievable media platform: I had access to people who wanted to tell my story to 20 million people. And so because of The Village Voice and 60 Minutes, it was the strangest thing to really call out the NYPD and have, like, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley call me and offer me investment banking jobs. It was such an odd thing. I walked away from a lot of really lucrative opportunities — it just didn’t make any sense with my soul, you know? But I also realized that I could use some of that attention and energy to shine a light in other spaces that needed it more. So the show that I’ve created [“Lyrics from Lockdown”] just came out of touring in prisons around the country, and it emerged from me having a relationship with somebody who was put on death row at 17 — a man named Nanon Williams. “Lyrics From Lockdown,” the show, came from “Lyrics On Lockdown,” the tour, which hit 25 states around the country and ended up as a course in several states. The one I saw was first at Columbia, then NYU, The New School and Rikers Island. So seeing this sort of growth in attention to these issues over the last decade or two decades has challenged me to think about how to find ways to make sure that we’re shining the light in the right place.

BB: We’re in a time where there’s more of a movement to do many of the things that some folks realized need[ed] to happen 20 years ago, but there was no movement in place. Without a mass social movement, it’s very difficult to make change that is lasting, systemic and happens at an institutional level. So that is the biggest difference. I finished law school and I had a really unbelievable media platform: I had access to people who wanted to tell my story to 20 million people. And so because of The Village Voice and 60 Minutes, it was the strangest thing to really call out the NYPD and have, like, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley call me and offer me investment banking jobs. It was such an odd thing. I walked away from a lot of really lucrative opportunities — it just didn’t make any sense with my soul, you know? But I also realized that I could use some of that attention and energy to shine a light in other spaces that needed it more. So the show that I’ve created [“Lyrics from Lockdown”] just came out of touring in prisons around the country, and it emerged from me having a relationship with somebody who was put on death row at 17 — a man named Nanon Williams. “Lyrics From Lockdown,” the show, came from “Lyrics On Lockdown,” the tour, which hit 25 states around the country and ended up as a course in several states. The one I saw was first at Columbia, then NYU, The New School and Rikers Island. So seeing this sort of growth in attention to these issues over the last decade or two decades has challenged me to think about how to find ways to make sure that we’re shining the light in the right place.

I was able to actually bring some attention to Nanon’s case a year after we had the first public performances of the show. A federal judge looked at his case again and decided he should be released. Now the state of Texas appealed. He’s still locked up over 25 years for crime he didn’t commit, but we are closer than ever to getting some movement on his case. Folks like Bryan Stevenson went before the Supreme Court and argued in a case called Sullivan v. Florida that young folks we have locked up all over the country doing life sentences without parole, their brains weren’t even fully developed when they were charged for these crimes and marked for the rest of their lives. They should have the opportunity to actually have redemption. It’s not even second chances: in many cases, it’s first chances. Folks live in communities where the choices are not the choices folks have in Beverly Hills, Brentwood, Bel Air and even Westwood, so that’s a big part of seeing this movement develop.

I feel like the folks that I’ve been blessed to work with have been a small part of building this larger movement because there weren’t editorials in The New York Times or the L.A. Times every week about mass incarceration. People weren’t even calling it “mass incarceration” or “hyper incarceration” or “racialized mass incarceration.” There was a network of folks — Critical Resistance through Angela Davis, a group called the Prison Moratorium Project, a group called the Malcolm X Grassroots Movement, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights — who were talking about the prison industrial complex, connecting the dots and realizing that our communities are being devastated by the drug war, by aggressive paramilitary policing, and by the human caging that is still impacting us. But there’s at least a conversation and a movement. Black Lives Matter is in part to thank for the more recent wave of that. So I think that’s the biggest difference: we’re having this conversation in a larger context.

It’s a different time now and there is a whole lot that has not changed and needs to change. But I think our consciousness is expanding. I think the voices of people who were formerly incarcerated and are currently incarcerated are moving toward the center of the movement where they should be. Whereas 20 years ago, most of the policy that was being generated around prisons and policing was being driven by folks who had no experience in our communities, or any of these correctional facilities where our communities have been put in unprecedented numbers.

A larger movement requires a holistic approach to the problem. A larger movement is not about just folks changing policy, or changing legislation even. One of the things I learned in law school is that if you don’t change the hearts and minds of people, then you’ve got to send the National Guard to make sure that little black girls can go to school in the South.

LD: I noticed that on the website for the Center for Justice, you say you’re “reshaping narratives through education, policy, research, advocacy, arts and culture.” Do you think that these are the channels through which we produce change?

BB: I think those are our essential areas. I think it’s hard to make systemic change without those areas being considered. I also think, at this location, at this time and place, those are areas that you cannot leave out of the equation because we’re in a city that has an impact on global culture: you have to think about the arts and culture. Because we’re in a Tier One research institution, you have to think about research and education policy. You have to think about those things because of where we are in the world, this time and place. So we’ve been able to think about and begin forging collaborations across the campus that actually do that. Last year we offered a course called Legislative Theatre For Racial Justice, about using the arts to shape policy. We have collaborations with the folks in World Arts and Cultures/Dance, the team at the Art & Global Health Center, the Law School, and African American Studies.

We brought a Brazilian visiting scholar, artist, and theatre-maker, Alessandro Conceição, from Brazil to work with us at the juvenile hall and to develop theater scenes – Theater of the Oppressed. I was introduced to this in law school, because I had a brilliant legal professor [Lani Guinier] who knew that the law is full of theatrics. She knew that the drama’s in every courtroom. But she also knew, practically speaking, that if you were to actually challenge young law students to think outside the box to say, “Okay, well, how are they creating legislation in Brazil?” and to get folks to act out the social problems they’re experiencing, and to actually propose solutions — not just to talk about or write about the solutions, but to act them out and have a dialogue around them — that might be something we could really use. And when I saw that, a light bulb went on, and I said, “this is what I’m supposed to be using.”

So to go to Brazil with our colleagues in World Arts and Cultures/Dance in December and actually begin a relationship between L.A. and Rio, which we hope to build over time and eventually send students and faculty back and forth — it was powerful. We had students at the juvenile hall tell their stories; do poetry; do theater. At the end of the course, in collaboration with UCLA students, they presented those scenes to legal scholars, judges, law clerks, a legislative brain trust, the UN Special Rapporteur against racism, in order to share those ideas, have a conversation, and then voted on legislative proposals that, through a training we just completed here at the [UCLA] Bunche Center, we’re now going to actually take to Sacramento and City Hall and work to have their voices be heard when usually their voices are never part of the process. So there’s a larger movement that made that possible. It’s also an opportunity to think outside the box, and to think about how we use the arts, theater, poetry, policy, research, and education and link those so they’re not siloed off in ways that there are seen to be irrelevant to each other.

Read Part 2 HERE

This interview has been edited for clarity.

LD: What do you [Professor Bain] tell people you do when you first meet them?

LD: What do you [Professor Bain] tell people you do when you first meet them?

BB: We’re in a time where there’s more of a movement to do many of the things that some folks realized need[ed] to happen 20 years ago, but there was no movement in place. Without a mass social movement, it’s very difficult to make change that is lasting, systemic and happens at an institutional level. So that is the biggest difference. I finished law school and I had a really unbelievable media platform: I had access to people who wanted to tell my story to 20 million people. And so because of

BB: We’re in a time where there’s more of a movement to do many of the things that some folks realized need[ed] to happen 20 years ago, but there was no movement in place. Without a mass social movement, it’s very difficult to make change that is lasting, systemic and happens at an institutional level. So that is the biggest difference. I finished law school and I had a really unbelievable media platform: I had access to people who wanted to tell my story to 20 million people. And so because of