Why Trump Can’t Have Tariffs and More Restrictions on Immigration

By Margaret E. Peters Assistant Professor, Political Science The…

Coming Out and “Outing Pigs”

By Abigail C. Saguy Professor of Sociology, UCLA In…

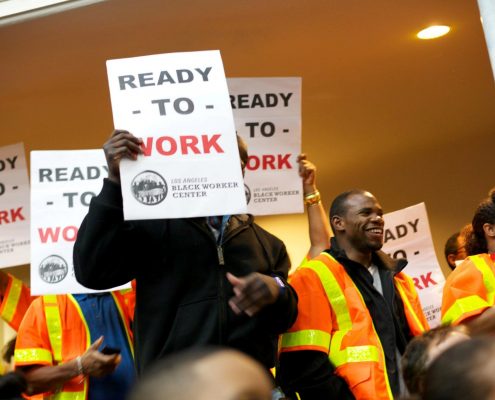

Ready to Work, Uprooting Inequity: Black Workers in Los Angeles and California

By Lola Smallwood-Cuevas, Project Director & Saba Waheed,…

Chronicling the Transformation of Black LA

By Marcus Anthony Hunter Scott Waugh Endowed Chair in…

Eavesdropping on Human Personality Variation: An Evolutionary Perspective

By Joseph H. Manson Professor of Anthropology Among our…

Mapping LA’s Million Dollar Hoods

By Kelly Lytle Hernandez Professor of History and African-American…