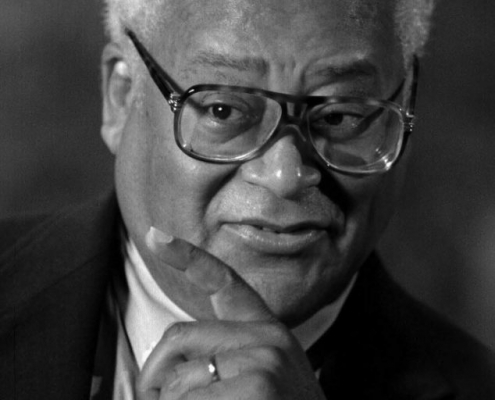

Celebrating Reverend Lawson’s Enduring Contributions at UCLA

By Kent Wong Director, UCLA Labor Center Rev. James…

A Case for Teaching Critical Media Literacy

By Rhonda Hammer, Lecturer, UCLA Department of Gender Studies We…

When They Call You a Criminal

By Rosie Rios, Administrative Director, UCLA Prison Education…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Dr. Karen Umemoto

Dr. Karen Umemoto is a professor in the Department of Asian…

Fear Is a Party Animal

By Sarah Gavish, UCLA Master of Social Science ‘18 In…

UCLA Dream Resource Center Sponsors Hackathon

By Kent Wong Director, UCLA Labor Center The UCLA Labor…

Word of Mouth: What an LA Auditory-Verbal Preschool Classroom Is Teaching Me About Spoken Language Development

By Kristella Montiegel PhD Student, Sociology, UCLA It’s…

Undocumented Stories Exhibit Visits Museum of Latin American Art

By George Chacon Dream Resource Center Project Manager,…

The Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey Welcomes Scholars From Around the Country to UCLA

UCLA looks forward to welcoming a diverse and inter-generational…

Do Legislative Bills Build Housing?

By Jan Breidenbach Senior Fellow, UCLA Department of Urban…