LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring UCLA Law Professor Jennifer Chacón

UCLA Law Professor, NYTimes op-ed author, and Latino Policy…

UCLA LPPI Brief Finds L.A. Black & Latino Neighborhoods Lack Resources During Safer-at-Home Order

On May 19, 2020, UCLA's Latino Policy and Politics Initiative,…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring UCLA Alum Karina Ramos (Video)

UCLA alum Karina Ramos ('99) an attorney at Immigrant Defenders…

UCLA California Policy Lab Releases Report on the Impact of COVID-19 on California’s Labor Market

New Analysis of Unemployment Insurance Claims in California Provides…

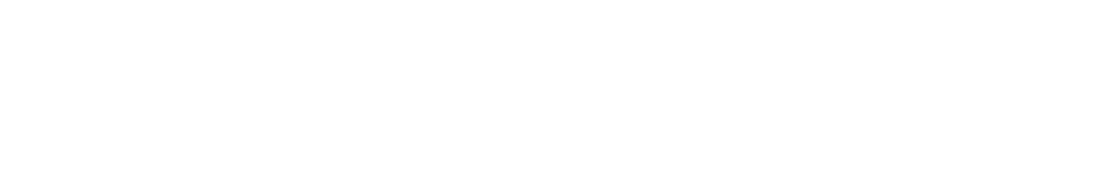

Pandemics Past and Present: One Hundred Years of California History

The UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy (LCHP) has…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Dr. Pedro Noguera (Video)

LA Social Science interviewed Dr. Pedro Noguera, Distinguished…

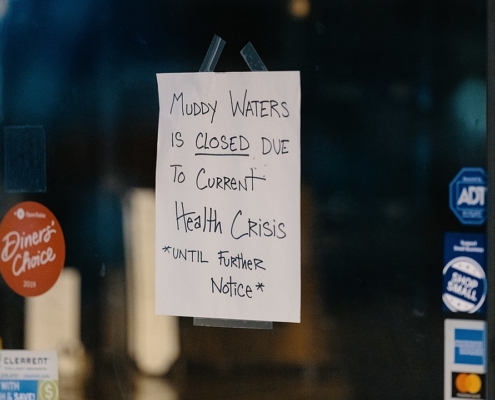

Pandemic Inequalities: Assessing the Fallout in the Restaurant Industry

By Eli R. Wilson, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University…

Then & Now: A New Podcast by the UCLA Luskin Center for History and Policy

The Luskin Center for History and Policy has created an exciting,…

The Coronavirus and the Humbling of America

Professor Vinay Lal, UCLA Professor of History and Asian…

A Scholar’s Journey to Change the World for the Better

Dr. Victor Agadjanian, UCLA professor with a joint appointment…