Posts

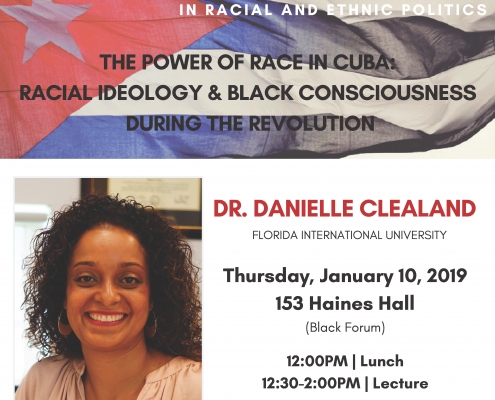

Recap of the Inaugural Sawyer Memorial Lecture in Racial and Ethnic Politics Featuring Dr. Clealand

The UCLA Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity and Politics…

SAVE THE DATE! Mark Q. Sawyer Memorial Lecture in Racial and Ethnic Politics on Thursday, January 10, 2019, 12:00-2:00 PM

***SAVE THE DATE***

The Inaugural Mark Q. Sawyer Memorial Lecture…

Students Participate in Collective Bargaining Exercise at UCLA

By Kent Wong Director, UCLA Labor Center The UCLA fall…

The Collaborative Multiracial Post-Election Survey Welcomes Scholars From Around the Country to UCLA

UCLA looks forward to welcoming a diverse and inter-generational…

Policing’s Role in Racial Segregation: 50 Years After the Fair Housing Act

By Rahim Kurwa Assistant Professor, University of Illinois…

PART 2: “Conversations with Changemakers” featuring Dr. Lorrie Frasure-Yokley

The following interview with Changemaker Dr. Lorrie Frasure-Yokley…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Dr. Lorrie Frasure-Yokley

Although the academic year is winding down, Dr. Lorrie Frasure-Yokley,…

Is Hollywood Leaving Money on the Table? Key Findings from the Hollywood Diversity Report 2018

The Hollywood Diversity Report 2018 is the fifth in a series…