The demonstration against government and corruption in the The demonstration against government and corruption in the Esplanada dos Ministerios (Marcello Casal Jr / Agência Brasil) (http://www.coha.org/combatting-grand-corruption-in-brazil/)

By Sergio Guedes Reis, UCLA Master of Social Science ‘18

Citizens all over the world consistently rank corruption as one of the most important public issues of our time. For instance, global market research firm IPSOS polled 21 thousand people from 28 countries and found that 35 percent of respondents cited corruption as the most important problem facing the globe today. A close second was ‘unemployment,’ which was mentioned by 34 percent of respondents.

In Brazil, a large-scale criminal investigation initiated in 2014 has unveiled a multi-billion dollar money laundering and bribery scandal involving almost every political party, as well as some of the major engineering and contracting firms and state-controlled oil companies. The subsequent political crisis ultimately led not only to the ousting of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016, but also a severe decline in people’s trust of institutions.

Interestingly, while narratives about the seemingly endemic nature of corruption in Brazil are widespread, polls suggest that actual levels of corruption may be much lower than the average rates found in other Latin American countries. That said, it is very hard to measure corruption, as it inherently happens under the radar. Taking this issue into account, watchdog organizations and survey companies usually look to gauge citizens’ perceptions of ongoing rates of corruption in their countries, ask local experts for their views on that matter, or even interview contractors about their experiences negotiating with public officers.

So in what circumstances do people accept engagement in corrupt activities or believe that corruption is positive? And why do Brazilians believe that corruption is their #1 problem, when polls consistently show that only a small percentage of citizens claim that they have had to bribe a public official themselves?

Based on this paradox, I decided to investigate what factors influence the tolerance for corruption in Brazil. After all, if so many people think corruption is a big problem in Brazil and nonetheless only a few admit engaging in corrupt practices, then it becomes crucial to understand whether certain conditions provide more room for corruption to happen than others.

In order to do so, I used two of the most recent Latin American surveys on public opinion, the 2016 Latinobarometer and the 2017 Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) surveys.

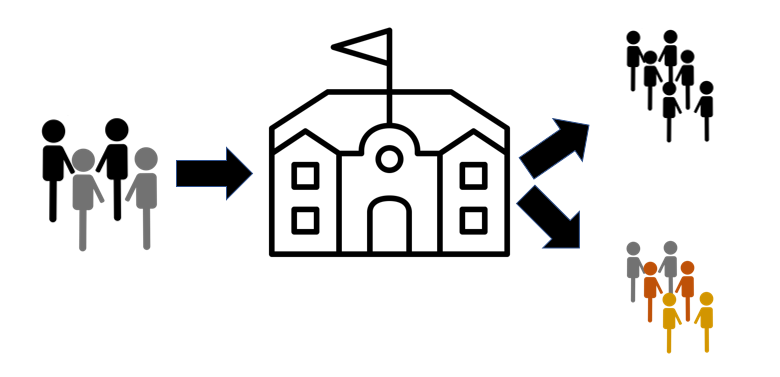

Then, I defined 3 basic forms of tolerance for corruption:

1) When citizens say they accept “corrupt, but efficient governments”

2) When they state that “bribing is sometimes acceptable”

3) When they declare that they do not feel personally obliged to report a case of corruption

There are several interpretations to why corruption exists in a society. For example, authors argue that people who advocate for authoritarian values are more prone to accept corruption, because they believe that being compliant with democratic procedures does not solve one’s own problems and thus people must take illegal, yet efficient action to achieve their goals. Others propose that low levels of trust (in other people and in institutions in general) are positively related to corruption, as discrediting others leads subjects to adopt more self-interested behavior to get things done.

I opted to test variables associated with these and other possible explanations in order to comprehend the issue at stake.

The most important findings I had were:

- Depending on the type of tolerance towards corruption, a different set of factors was more strongly associated with it. Variables associated with authoritarian values and socio-economic and demographic attributes (such as low development, high income and inequality) were more correlated with acceptance of corrupt (but efficient) governments, justification of bribery, and low levels of trust with avoidance of reporting cases of corruption.

- Individuals who trusted in people in general, had confidence in certain institutions or were well informed about them (the Parliament, political parties, and even groups from civil society) were also more prone to accept corruption.

- Citizens who stated they believed in typical markers of the status quo (such as claims about the fairness in the distribution of income, the impartiality of the Judiciary branch or the existence of equality of opportunity among Brazilians) were also more likely to accept corruption.

Survey-based research can usually only capture subjects’ opinions regarding a given topic, and not their actual practices. So, it is not possible to state that a moral agreement with corruption would imply acting corruptly in a real setting. Nonetheless, a pro-corrupt attitude may represent an open door for the occurrence of rule violations if the context allows. In the Brazilian case, the presence of structural factors (such as inequality and developmental levels) as predictors of tolerance towards corruption suggest this issue to have deep roots in the country’s social fabric. It also indicates that anticorruption solutions need to be connected to welfare and redistribution policies if they are to become more efficient and effective.

Future research considering other countries, cultures and contexts may disentangle other factors and particular mechanisms through which corruption becomes an acceptable enterprise. For Brazil, at least, it seems that fostering democratic values, political accountability, social equality and education would offer a way out of the large-scale turmoil it currently faces.

Sergio Guedes Reis is a Federal Auditor at the Brazilian Ministry of Transparency and a 2018 graduate of UCLA’s Master of Social Science (MaSS) program.

Sarah Gavish is a social scientist interested in solving humanity’s problems through conversation, collaboration, and an eventual upheaval of unquestionably flawed cultural institutions. She also likes to meditate, cook, argue, and read books. Sarah is not on social media and is happy to explain why (you shouldn’t be either)

Sarah Gavish is a social scientist interested in solving humanity’s problems through conversation, collaboration, and an eventual upheaval of unquestionably flawed cultural institutions. She also likes to meditate, cook, argue, and read books. Sarah is not on social media and is happy to explain why (you shouldn’t be either)