Pandemic Inequalities: Assessing the Fallout in the Restaurant Industry

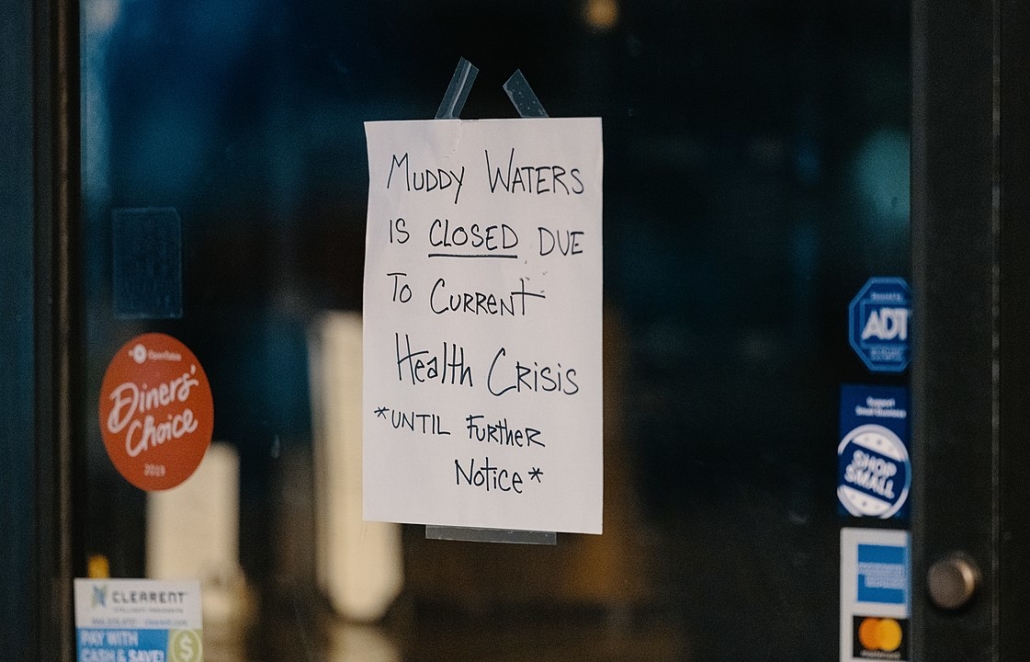

Photo Credit: Tony Webster from Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States – Closed Due to Health Crisis, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=88247255

By Eli R. Wilson, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of New Mexico

It is impossible to locate a part of our society that has not been profoundly affected by the current pandemic, as we lurch from health crisis to economic crisis to labor crisis to community crisis—and back again.

The U.S. service sector remains at the epicenter of the crisis. The California Restaurant Association recently issued a dire warning that 30% of restaurants in the state will close without dramatic government intervention. In a letter to the governor, the group argues that the recent federal aid package is a Band-Aid that will not prevent permanent closures. Hundreds of thousands of restaurant workers have already filed for unemployment, and anticipated job losses in the industry are running as high as 7 million. The Restaurant Opportunity Center (ROC), a worker advocacy group, is one of several organizations that have set up an emergency relief fund to help the most desperate families.

The effects of the pandemic on the restaurant industry has been uneven, with a much larger impact on small businesses and vulnerable workers. On the business side, many of the immediate closures are mom-and-pop restaurants, which are disproportionately owned by immigrants and people of color. Restaurants operate on razor-thin 5–10% profit margins even in good times, so many smaller restaurants make just enough money to stay afloat month to month. The $2 trillion federal aid package will supposedly reach these types of businesses, but accounting for inevitable processing delays and the continuation of government-mandated closures across the country, it may be too little, too late.

Among restaurant employees, undocumented workers find themselves in particularly dire straits. Without proper work authorization, these individuals cannot seek federal assistance, including funds from the federal aid package, despite being laid off and having paid into the taxes that are funding that aid. Prior to the pandemic, the industry’s millions of undocumented workers were already a largely invisible group employed mainly in physically taxing back-of-the-house jobs with low wages and few benefits. Reduced work hours and widespread layoffs will push many to grapple with the inability to meet their family’s basic needs and nowhere to turn for help but friends and relatives in equally precarious situations.

At the same time, the most dramatic relative impacts on restaurant workers are on front-of-the-house workers, who tend to be young, white, and middle-class. Socially speaking, this is not an at-risk group. Yet because of the structure of their jobs, the pandemic is nothing short of an employment Armageddon for the nation’s nearly 4 million servers, bartenders, baristas, hosts, and cashiers. Front-of-the-house employees’ work schedules are directly related to customer traffic; fewer customers mean fewer hours of work in the dining room. Also, front-of-the-house workers rely heavily on tips for their income. Normally, these workers expect that a steady stream of diners will pad their low hourly wages, and servers and bartenders at higher-end restaurants can make $15-30 per hour in tips on top of their base wages. So even if some restaurants are able to maintain employee payroll during this period, without customers or tips, these workers will find themselves among the lowest-paid in the country.

A few restaurants are staying busy through a mixture of the right business model (quick-serve, takeout) and the resources to adjust to the months-long closure of dining room service. But neither describes the majority of sit-down restaurants, especially small ones. At best, this is the end of a golden age for restaurants in terms of growth and profits (one that weathered the 2007–2009 Great Recession relatively well). At worst, this crisis has laid bare a broken industry paradigm with no safety net for millions of workers and left small restaurants fighting for their survival.

We need to push for federal and state-level aid crafted by policy makers in collaboration with restaurant industry leaders to ensure that aid is distributed both efficiently and equitably. A significant portion of this money should be flagged for small businesses trying to meet operating expenses and employee payroll. Temporary policy changes can help too, such as recent city-level decisions to allow restaurants to sell groceries and to-go alcohol (with the appropriate liquor license). On an individual level, every consumer who is financially able should do their part to support their local restaurants as much as possible. Buy takeout regularly from these establishments, tip delivery people well, purchase gift cards. We want to ensure that when the effects of this pandemic subside, our neighborhood gathering places and those who work in them are able to rebound as quickly as possible.

Eli Revelle Yano Wilson is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of New Mexico. He received his PhD from the University of California, Los Angeles, and is a former research affiliate with the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. Dr. Wilson studies labor dynamics within the U.S. restaurant and the craft beer industries. His first book, Front of the House, Back of the House: Race and Inequality in the Lives of Restaurant Workers, will be released this fall through NYU Press.

Eli Revelle Yano Wilson is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of New Mexico. He received his PhD from the University of California, Los Angeles, and is a former research affiliate with the UCLA Institute for Research on Labor and Employment. Dr. Wilson studies labor dynamics within the U.S. restaurant and the craft beer industries. His first book, Front of the House, Back of the House: Race and Inequality in the Lives of Restaurant Workers, will be released this fall through NYU Press.

Subscribe to LA Social Science and be the first to learn more insight and knowledge from UCLA social science experts in upcoming video/audio sessions and posts dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic.