UCLA California Center for Population Research Commemorates Its 20th Anniversary

On October 11-12, 2018, the California Center for Population…

UCLA Professor Frasure-Yokley Discusses Her Electoral Research on MSNBC — Watch Video Here

On October 8, UCLA Professor Lorrie Frasure-Yokley and UCLA…

UCLA Professor Menjivar Scheduled to Speak at DWC Congressional Briefing on 10/11

On October 11, Professor Cecilia Menjivar will discuss asylum…

What Does the L.A. Valley Girl Stereotype Say About Language and Power?

By Tyanna Slobe PhD student, Linguistic Anthropology,…

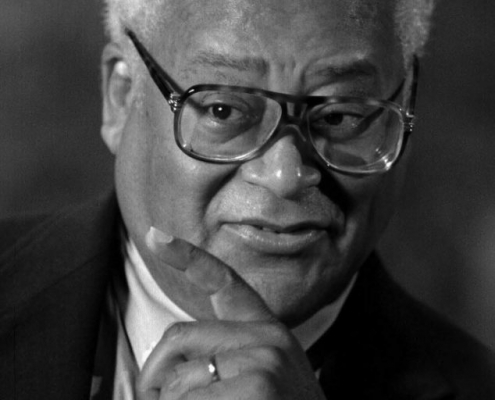

Celebrating Reverend Lawson’s Enduring Contributions at UCLA

By Kent Wong Director, UCLA Labor Center Rev. James…

A Case for Teaching Critical Media Literacy

By Rhonda Hammer, Lecturer, UCLA Department of Gender Studies We…

When They Call You a Criminal

By Rosie Rios, Administrative Director, UCLA Prison Education…

Storytelling For Self and Community Healing – UCLA Event Tomorrow 9/27

A Conversation with Dr. Beth Ribet, Co-Director and Co-Founder…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Dr. Karen Umemoto

Dr. Karen Umemoto is a professor in the Department of Asian…

Fear Is a Party Animal

By Sarah Gavish, UCLA Master of Social Science ‘18 In…