Posts

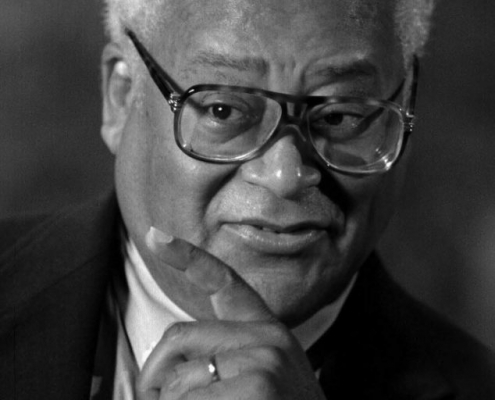

Celebrating Reverend Lawson’s Enduring Contributions at UCLA

By Kent Wong Director, UCLA Labor Center Rev. James…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Dr. Bill Worger

Dr. Bill Worger, Professor of History at UCLA, is working…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Dr. Lorrie Frasure-Yokley

Although the academic year is winding down, Dr. Lorrie Frasure-Yokley,…