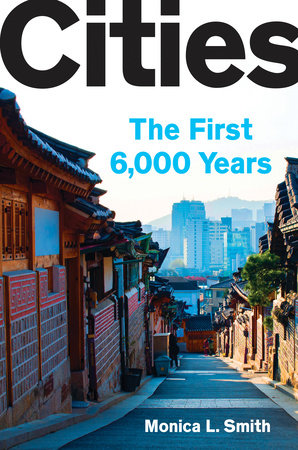

Monica L. Smith is a UCLA professor in the Department of Anthropology. In addition to teaching and mentoring students, Smith is the Navin and Pratima Doshi Chair in Indian Studies and the Director of South Asian Archaeology Laboratory in the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. Her principal research interests have three main focuses: the human interaction with material culture, urbanism as a long-term human phenomenon, and the development of social complexity. Most recently, Smith has spent time on a research project in eastern India, but her scope of work covers various parts of the world including Madagascar, Turkey, Bangladesh, Italy, Tunisia, Egypt, and the United States to name a few. Smith has combined her years of rich research and experience to share the history of cities in her newly published book that was released this month titled, Cities: The First 6,000 Years. In a recent correspondence with Smith she describes in her own words a brief comment about her book. She explains:

“This book explores what makes cities a compelling part of human life, and how over the past six thousand years they have become the dominant form of human settlement. The growth of cities wasn’t an easy process and those who live in cities find them challenging and exciting in equal measure. There is crowding, pollution, high prices, and traffic, but at the same time there are amazing job opportunities, educational and medical facilities, and the possibilities of entertainment ranging from major sports teams to museums, art galleries, and theaters. Cities are also places of much greater diversity, whether that’s ethnic diversity, migrant neighborhoods, or LGBTQ communities. Cities are places of great economic growth and they’re linked together into a global network of connected places.”

“This book explores what makes cities a compelling part of human life, and how over the past six thousand years they have become the dominant form of human settlement. The growth of cities wasn’t an easy process and those who live in cities find them challenging and exciting in equal measure. There is crowding, pollution, high prices, and traffic, but at the same time there are amazing job opportunities, educational and medical facilities, and the possibilities of entertainment ranging from major sports teams to museums, art galleries, and theaters. Cities are also places of much greater diversity, whether that’s ethnic diversity, migrant neighborhoods, or LGBTQ communities. Cities are places of great economic growth and they’re linked together into a global network of connected places.”

Dr. Smith offered additional insights and words of wisdom in a short series of questions about her book.

What inspired you to write your book, Cities: The First 6,000 Years?

I really enjoy teaching my classes “Cities Past and Present” and “Religion and Urbanism” within the Anthropology Department here at UCLA. And I am also an archaeologist who works on ancient urban centers in the Indian subcontinent. Those experiences, as well as my interest in contemporary cities (including our great city of LA!) provided the inspiration for the book. There are a lot of things about cities that we find challenging, but cities are growing larger and larger. My interest was in exploring the long continuity of city life from the very beginnings of urbanism starting six thousand years ago right through to the present and future.

How long did the process take to complete your book?

The Cities book was a sequel to a previous book that I wrote, A Prehistory of Ordinary People, which was published in 2010. Like most academic projects, there’s a kernel of an idea that starts long before we sit down to write a new book. But this one took a couple of years, which in terms of increments is not that much work – about a page a day, really, although some of those pages were rewritten many times to try and get it just right.

What were some of the challenges of writing and publishing?

I was very fortunate in having good prior experiences in public engagement such as through the UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology’s annual Backdirt publication. And my colleague Jared Diamond (UCLA Geography) was very helpful in providing encouragement and suggestions. The publication staff and editors at Viking Press were amazing in their dedication to the book and in support of me as an author.

What was most enjoyable about writing this book?

As I wrote in the book’s acknowledgements, this book was really a pleasure to work on and something that I truly enjoyed doing. I’ve always been interested in examining archaeology beyond the perspective of palaces, kings, and queens, so it was an opportunity to think about how we can take evidence in the form of potsherds and ancient buildings to understand how ancient people felt about their cities and how those feelings are still part of our own urban lives.

What do you hope readers take from your book?

I enjoyed the idea of walking people through their own cities, so that they can be archaeologists too. There are the physical remains of our ancestors everywhere around us in every city; in Los Angeles, we have places like Olvera Street and Sawtelle Japantown and Bruce’s Beach. Once people start to look around at the palimpsests of the past in their own city, they can apply those skills to the places that they visit in their travels or the cities to which they relocate for work and family. Cities are remarkably similar in time and space, whether they are archaeological sites or living cities. And some places, like Rome and Mexico City, are ancient and modern all at the same time.

Any advice for others (students/professors) who want to write their own book?

Writing a book isn’t much different from writing a paper (a very long paper!).

How were you able to balance so many responsibilities in your personal life with family and as a professor, chair, director, as well as author a book?

As faculty, we are constantly writing in a variety of different formats, including writing research articles, grant proposals, conference papers, and letters of recommendation in support of students. So, writing a book gets folded into those other activities, and writing is a little bit like breathing: something that we do all the time. But I’ll admit that one of the things that gets cut in the balance of activities is keeping up with things like movies and TV, so I rely on my friends to keep me up to date on that!

How do you feel now that your book is out? How has it been received?

The publisher has been great about spreading the word, and the reviews in advance of publication have been beautiful. One thing that I really appreciated was the reviewers who found the book “humorous” which is not something that faculty often hear – it’s a great compliment. I hope that people enjoy reading it, even if they have time for just a chapter or two.

Definitively, Smith’s book has resonated with many people and has been recognized by other authors, archaeologists, colleagues, and publishing companies. Below are just a couple of praises Smith has received regarding her book. Zahi Hawass, author of Hidden Treasures of Ancient Egypt stated, “Cities captures the reality and stress of how we make cities and how, sometimes, cities make us. This is a must-read book for any city dweller with a voracious appetite for understanding the wonders of cities and why we’re so attracted to them.” Similarly, Publishers Weekly commented on Smith’s book saying it was, “[An] enjoyable, humorous combination of archeological findings, historical documents, and present-day experiences.” These are convincing reviews, so get the book and read it for yourself.

To read additional reviews and media coverage on Cities: The First 6,000 Years, check out these sites: Simon & Schuster, Penguin Random House, Centre for Cities, WAMC Northeast Public Radio, and The American Scholar.