Bargaining for the Common Good: An Analysis of the Los Angeles Teachers’ Strike

By Betty Hung, Staff Director, and Kent Wong, Director, UCLA…

UCLA Lecturer Works as Lead Attorney on Texas Voter Purge Case

These last two weeks, a court in San Antonio, Texas has taken…

Testimony on Voting Rights Issues

The U.S. House Committee on Administration was authorized…

Growing Up Bilingual in Multilingual Los Angeles

By Lilit Ghazaryan UCLA Graduate Student, Department of…

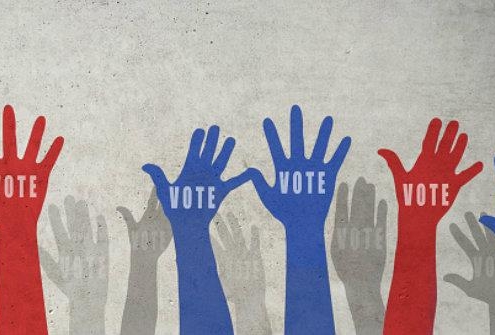

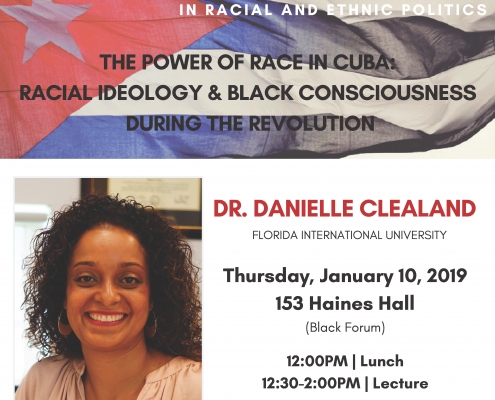

Recap of the Inaugural Sawyer Memorial Lecture in Racial and Ethnic Politics Featuring Dr. Clealand

The UCLA Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity and Politics…

SAVE THE DATE! Mark Q. Sawyer Memorial Lecture in Racial and Ethnic Politics on Thursday, January 10, 2019, 12:00-2:00 PM

***SAVE THE DATE***

The Inaugural Mark Q. Sawyer Memorial Lecture…

Launch of the “Women Beyond Bars: Reentry and Human Rights” Report — TOMORROW at UCLA

Congratulations to UCLA Associate Professor, Bryonn Bain, for…

Defending Voting Rights: A Civil Rights and Social Science Partnership in Action

By Chad Dunn, Brazil & Dunn, Attorneys at Law, and Matt…

Students Participate in Collective Bargaining Exercise at UCLA

By Kent Wong Director, UCLA Labor Center The UCLA fall…

LA Social Science Presents “Conversations with Changemakers” Featuring Bryonn Bain and Rosie Rios – Part 2

By Lara Drasin Read Part 1 of this interview HERE. Bryonn…