Inverted Relationships: Humans and Dogs in the Times of Coronavirus Anxiety

Photo Credit: Aonip/iStock (https://www.marketwatch.com/story/can-my-cat-get-coronavirus-should-my-dog-wear-a-mask-what-pet-owners-need-to-know-about-covid-19-2020-04-10)

Professor Vinay Lal, UCLA Professor of History and Asian American Studies, has an informative blog titled, “Lal Salaam: A Blog by Vinay Lal.” Recently, he has written “a series of articles on the implications of the coronavirus for our times, for human history, and for the fate of the earth.”

You may read his earlier essays on LA Social Science. The following is a full reprinting of his fifth essay, “Inverted Relationships: Humans and Dogs in the Times of Coronavirus Anxiety,” (April 11, 2020), in the series:

Around a month ago, when schools, colleges, and universities began to transition to online learning, and the first edicts for the closure of museums, restaurants, and other public places were put into effect, some pet owners began to ponder whether social distancing also required them to keep their pets at arm’s length. Though COVID-19 is of zoonotic origins, having, most likely, been transmitted from a coronavirus-infected horseshoe bat to humans via another animal—the pangolin has been mentioned as the most likely host—the present strain of the coronavirus did not at first appear to transmit from humans to dogs, cats, and other domestic animals. In late February, however, a 17-year old Pomeranian, whose owner had been infected, also tested positive for the coronavirus and passed away in mid-March, though the exact cause of its death is uncertain and will be not known as its owner did not permit an autopsy; a second dog, a German shepherd, tested positive but remained asymptomatic. Then, more recently, a domestic cat in Belgium became infected but recovered after nine days.

As the coronavirus pandemic rages on, shuttering the economy around the globe, leaving tens of millions without jobs security, eviscerating commonly held notions about “public culture”, altogether emptying out public spaces, and, most critically, leaving in its wake a devastating and still continuing toll of human lives and suffering, it may seem to some a luxury to revisit in light of the profound changes that the pandemic has already wrought in everyday life the manner in which we understand the relationship of human beings to animals and in particular domestic pets. However, much in recent times has brought us to an enhanced awareness both of the staggering diversity in the non-human world, and the sheer peril in which animals, birds, and entire ecosystems have been placed in consequence of human activity and the unfortunately commonly held view that human beings have every right to exercise dominion over nature. Beyond this more, as would (mistakenly) say, abstract view, there is this consideration which suggests why thinking of domestic pets at this juncture may yield some insights into the present predicament: 60 per cent of American households have at least one pet, and 44 percent of Americans own a dog. One may be certain that pet owners have had much occasion to think not only about whether their pets might be susceptible to COVID-19 but the comforts (and to some the hazards) of pet ownership at such a time. Pet owners, largely reduced like everyone else to the confines of their home, are doubtless spending a good deal more of their time with their pets; in my neighborhood in Los Angeles county, as I saunter along on my evening walks during these days of lockdown, I am encountering neighbors walking their dogs whom I have never seen before in nearly twenty years at the same address.

A recent Los Angeles Times article, “Man’s best friends during crisis”, suggests that people from around the world are discovering anew the joys of pet ownership, and in particular dogs, as the pandemic keeps them largely immobilized at home. Hospitals, even in “ordinary” times, have been known to use dogs as part of therapy treatments, and at this time of acute anxiety the comfort humans appear to derive from the companionship of dogs has become all the more palpable. Animal shelters are reporting an unusually high interest in the adoption of abandoned dogs and cats, and not only in the United States. “Amid the lockdown,” notes the Los Angeles Times article in the syrupy language which characterizes much writing on domestic pets, “a restless and hard-headed nation has discovered that what it really needs right now is a snuggle and slurp.” To some a new pet represents hope, indeed a vigorous affirmation of the idea that “life goes on” and that “all is well”, or will be well; to others the pet is, much like Netflix, a pleasant distraction from the doom and gloom of the news hour. For working parents now unexpectedly saddled with small children, a domestic pet may even have the same quality of serving in loco parentis long associated with school teachers.

As the coronavirus pandemic carries on, and once we are past it, we will doubtless get to know more about how dogs (and cats) have fared in different cultural milieus. Sassafras Lowery, a “Certified Dog Trick Instructor” who has written recently for the New York Times, noted that she was struck by the considerably different behavior exhibited by dogs in European countries—Britain, Germany, France, and the Netherlands—in contrast to the United States. She found that in Europe “dogs are everywhere”, in restaurants, bars, theaters, buses, and trains among other public venues, and they seemed welcome and thus “calm, relaxed and quiet”; in the United States, on the other hand, “pet dogs aren’t welcome in most public spaces, and often struggle in the public places where they are allowed.” If dogs seem better integrated into the culture of everyday life in “ordinary times” more so in some European countries than in the United States, it would be interesting to know whether in a post-pandemic society the relationship between dogs and their owners might not also change. Lowery goes on to suggest, tellingly, that “dog behavior isn’t all about the dogs. A lot of it has to do with us.”

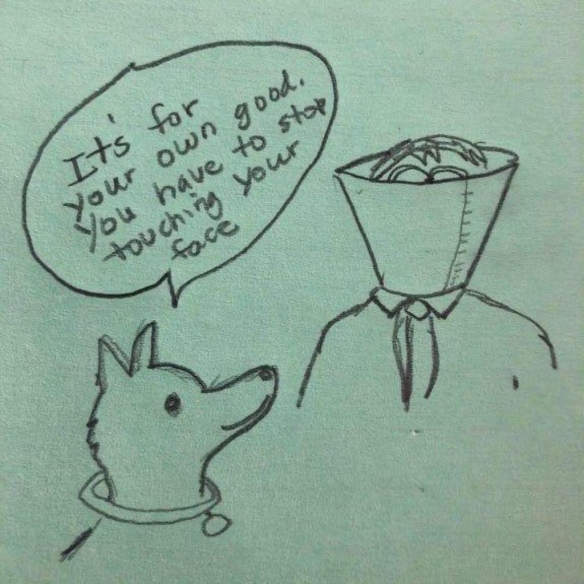

There is a long history of the anthropomorphization of disease and it should not surprise us if cartoonists have been busy sketching the Grim Reaper in our midst. But the skillful cartoonist can just as easily with a few line drawings render any subject both vivid and complex at the same time, and in these times of coronavirus anxiety some of them have with great sensitivity suggested the inverted relationships of humans to dogs. I would like to take up for brief discussion three cartoons shared with me from friends in India through the popular messaging service, WhatsApp. In the first, just as the dog is about to leave home to paint the town red, he says to his owner: “Be Good . . . Back Soon!”

This cartoon requires, most people would say, no interpretation. Even those who are not dog owners are entirely familiar with the scenario: as the owner leaves home, he or she speaks to their dog as they would to their child: be good, don’t mess up the place too much, and don’t do anything naughty. Now the dog owner has been put in that place, indeed he has been put, the dog appears to be saying rather gleefully, in his place: the inversion is only possible because humans are now commanded to stay indoors and must surrender the exterior space to the lower species. The cartoon plays upon notions of interiority and exteriority; but it also tugs at notions of freedom and restraint. The leash that remains upon the dog’s neck suggests that the Bacchanalian excess in which the dog might indulge is but momentary: it is something akin to the carnivalesque but temporary inversion of the social order that Mikhail Bakhtin, in his book on Dostoevsky’s Poetics, described as characteristic of the middle ages, a phenomenon also witnessed by anthropologists in many societies. A similar set of ideas are conveyed in a second cartoon: the dog is hectoring his owner, reminding him that the constraints that have

been placed upon him are for his own good. But this cartoon takes further the assault on man’s real or supposed distinction from all other species in being able to command the faculty of reason: we think we are by far the higher species on account of our ability to reason, exercise restraint, and discipline ourselves, but we are fundamentally creatures of habit.

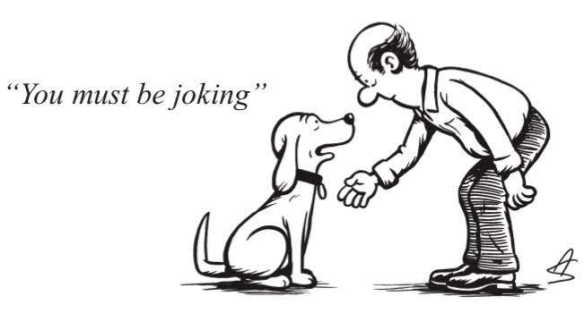

“You must be joking,” says the dog to a man who has extended his hand for the customary dog handshake. Are you trying to give me the virus, the dog asks with an incredulous look on his face. We always expect dogs to take our extended hand: the dog

that does so is a “gentleman”, a good dog, a friendly family dog. In these times of the pandemic, the dog can be daring and reject that extended (and often unwittingly condescending) hand. The behavioral anthropologists at least must be convinced that the handshake originated as a greeting between two parties that were keen to show each other that they were willing to greet each other, and come to the negotiating table, without arms. Somewhere there must be a social or cultural historian who has written on the handshake, but we do know that in countries such as India the handshake came as a colonial artefact. Indeed, Hindu nationalists have been cowing in recent weeks of the now evident superiority, as they point out, of the traditional greeting in India, the namaskar which entails bringing the palms together before one’s and bowing. Not less elegant, they may be reminded, is the adab of South Asian Muslims.

Every dog has its day, says an old English proverb that Shakespeare chewed on to render it thus:

Let Hercules himself do what he may,

The cat will mew and dog will have his day. (Hamlet, V.i)

As the coronavirus pandemic continues to wag its tail in our face, every dog is surely having his day.

Subscribe to LA Social Science and be the first to learn more insight and knowledge from UCLA social science experts in upcoming video/audio sessions and posts dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic.